Lynchpin of Middle Eastern politics

Hi eveyone, t's been a while...

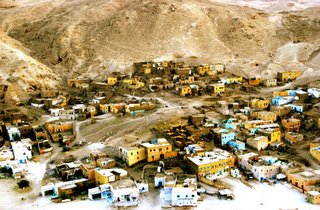

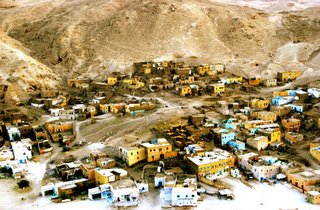

Find below a very interesting piece of article (written by Paola Caridi www.lettera22.it form the independent journalist association) to give you a better insight on the extremely complex situation in the middle east, and the difficult and strategic relationship with the US. I added a couple of pictures of the recent trips to relax your eyes and (hopefully) make you jealous...hehe

Nation of strategic importance. Element of regional stability. In the view of American foreign policy for the Middle East and North Africa over the last thirty years, Egypt has merited mostly flattering comments on the regional role it has played. And all things considered, the compliments have reflected what Egypt has really meant to the USA’s political strategies towards the Middle East, the Arab nations, and the whole region. Including Iran. If only because, in that part of the world, the alliance with Egypt has been the most important and most unexpected diplomatic success, the Department of State and the White House’s prize exhibit from the last fifty years. Made possible, for the most part, by the presence as Egyptian leader of a statesman capable of making astonishing choices, Anwar el Sadat. Protagonist of a drastic change in alliance after the 1973 war, and of an equally sudden abandonment of traditional Nasserite foreign policy which had as its three fundamental pillars the Soviet Union, the Non-Aligned movement, and pan-Arabism.

Nation of strategic importance. Element of regional stability. In the view of American foreign policy for the Middle East and North Africa over the last thirty years, Egypt has merited mostly flattering comments on the regional role it has played. And all things considered, the compliments have reflected what Egypt has really meant to the USA’s political strategies towards the Middle East, the Arab nations, and the whole region. Including Iran. If only because, in that part of the world, the alliance with Egypt has been the most important and most unexpected diplomatic success, the Department of State and the White House’s prize exhibit from the last fifty years. Made possible, for the most part, by the presence as Egyptian leader of a statesman capable of making astonishing choices, Anwar el Sadat. Protagonist of a drastic change in alliance after the 1973 war, and of an equally sudden abandonment of traditional Nasserite foreign policy which had as its three fundamental pillars the Soviet Union, the Non-Aligned movement, and pan-Arabism. While it is true to say that Sadat’s presence was essential to Washington considering Cairo as its Arabian bridgehead in the Middle East and North Africa, one has to admit that the alliance between the United States and Egypt has succeeded in surviving without Sadat, and above all in surviving various political earthquakes in the region that could have damaged the alliance’s stability and indeed destroyed the entire relationship between Cairo and Washington. But despite initial misgivings, despite the difference in character between himself and Sadat, and the difference between their conceptions of Egypt’s political role, Hosni Mubarak has nonetheless managed to maintain the commitments made by his predecessor. That’s to say, he has managed to preserve the alliance with the United States. Although in different terms than those foreseen by Washington. And it may well be that Washington has benefited from the changes that Mubarak has imposed during his twenty years of rule, in some cases without its ally’s approval.

While it is true to say that Sadat’s presence was essential to Washington considering Cairo as its Arabian bridgehead in the Middle East and North Africa, one has to admit that the alliance between the United States and Egypt has succeeded in surviving without Sadat, and above all in surviving various political earthquakes in the region that could have damaged the alliance’s stability and indeed destroyed the entire relationship between Cairo and Washington. But despite initial misgivings, despite the difference in character between himself and Sadat, and the difference between their conceptions of Egypt’s political role, Hosni Mubarak has nonetheless managed to maintain the commitments made by his predecessor. That’s to say, he has managed to preserve the alliance with the United States. Although in different terms than those foreseen by Washington. And it may well be that Washington has benefited from the changes that Mubarak has imposed during his twenty years of rule, in some cases without its ally’s approval. The relation between Egypt and the United States was founded on certain premises, but these soon evolved in ways that corresponded more to Egypt’s than to America’s strategy. The final balance, after twenty years of Mubarak’s presidency, is nonetheless positive for both partners in the alliance. The United States have had in Egypt the lynchpin of its foreign policy for the region, based on four priorities. Firstly, guaranteeing safe passage for crude oil from the Persian Gulf through the Suez Canal. Secondly, protecting the security of Israel. Thirdly, containing those nations in the region which, at different moments, have most threatened American interests (Iran and Iraq). And finally, during the first half of these twenty years at any rate, limiting the influence of the Soviet Union and exporting the policy of global containment to the Middle East and North Africa.

The relation between Egypt and the United States was founded on certain premises, but these soon evolved in ways that corresponded more to Egypt’s than to America’s strategy. The final balance, after twenty years of Mubarak’s presidency, is nonetheless positive for both partners in the alliance. The United States have had in Egypt the lynchpin of its foreign policy for the region, based on four priorities. Firstly, guaranteeing safe passage for crude oil from the Persian Gulf through the Suez Canal. Secondly, protecting the security of Israel. Thirdly, containing those nations in the region which, at different moments, have most threatened American interests (Iran and Iraq). And finally, during the first half of these twenty years at any rate, limiting the influence of the Soviet Union and exporting the policy of global containment to the Middle East and North Africa. Mubarak’s regime too, from its point of view, has obtained more positive than negative results from maintaining the alliance with the United States. On the one hand, as a reward for its role as a bridgehead, it has continued to benefit from the largest economic aid package dispensed by America in the whole area, indispensable for the country’s internal stability. On the other, in an analysis that is only apparently paradoxical, it has exploited its privileged relation with the Americans to gradually revive and reinforce its own position within the Arab world.

Mubarak’s regime too, from its point of view, has obtained more positive than negative results from maintaining the alliance with the United States. On the one hand, as a reward for its role as a bridgehead, it has continued to benefit from the largest economic aid package dispensed by America in the whole area, indispensable for the country’s internal stability. On the other, in an analysis that is only apparently paradoxical, it has exploited its privileged relation with the Americans to gradually revive and reinforce its own position within the Arab world. All things considered, therefore, this has been an alliance that has given satisfaction to both partners. Despite its ups and downs, and despite the changes which the United States could never have foreseen at the time when Sadat put himself decisively in the American camp and carried out the two principal acts of his presidency: the leap from one side of the Iron Curtain to the other, and the peace with Israel. The Americans could never have imagined that Sadat would have disappeared from the scene so soon, and in such a sudden and tragic way. They therefore witnessed Mubarak’s coming to power with considerable scepticism, based on what they knew of him from his visits to the US as vice-president before Sadat’s assassination. During which Mubarak had shown himself to be quite different from his president. Less brilliant, in the first place, both in public and in private. Among American politicians and political technicians the main fear was that Mubarak “was seen as demanding, somewhat abrasive and unbending”, as Hermann Frederick Eilts has written. The worry was, in other words, that Mubarak would not have honoured the peace with Israel, still in its infancy, and might even have returned to the path set down by Gamel Abdel Nasser.Were these worries founded? History informs us that, as it turns out, Mubarak has respected the commitments made by Sadat, showing an unexpected degree of loyalty. But he has done so without his predecessor’s enthusiasm. Without Sadat’s open and passionate conviction. Whereas the former defied the entire Arab world by making a state visit to Jerusalem, the latter went there only for the funeral of Ytzhak Rabin, in November1995. In profoundly different circumstances, with Mubarak having only recently managed to re-enter the diplomatic manoeuvres surrounding the Oslo Agreements (from which he had been excluded). And in a regional context where the impetuous winds of change of Oslo, the handshake between Yasser Arafat and Ytzhak Rabin, and the 1991 Gulf War, had long since petered out. Mubarak has always done his duty towards the alliance with America, but without overdoing things. Indeed, especially in the second part of his first 2 decades in power, being always careful not to lose touch with the mood of the Egyptian man in the street and shifts in the internal political situation, in contrast to Anwar el Sadat, who paid with his life for his inability to understand what was happening in radical Islamic circles. To use the words of Ali Hillal Dessouki, on a national level Mubarak’s foreign policy “did not replace Sadat’s, but worked paralleled to it, with the aim of balancing the side-effects of his predecessor’s policies”.

All things considered, therefore, this has been an alliance that has given satisfaction to both partners. Despite its ups and downs, and despite the changes which the United States could never have foreseen at the time when Sadat put himself decisively in the American camp and carried out the two principal acts of his presidency: the leap from one side of the Iron Curtain to the other, and the peace with Israel. The Americans could never have imagined that Sadat would have disappeared from the scene so soon, and in such a sudden and tragic way. They therefore witnessed Mubarak’s coming to power with considerable scepticism, based on what they knew of him from his visits to the US as vice-president before Sadat’s assassination. During which Mubarak had shown himself to be quite different from his president. Less brilliant, in the first place, both in public and in private. Among American politicians and political technicians the main fear was that Mubarak “was seen as demanding, somewhat abrasive and unbending”, as Hermann Frederick Eilts has written. The worry was, in other words, that Mubarak would not have honoured the peace with Israel, still in its infancy, and might even have returned to the path set down by Gamel Abdel Nasser.Were these worries founded? History informs us that, as it turns out, Mubarak has respected the commitments made by Sadat, showing an unexpected degree of loyalty. But he has done so without his predecessor’s enthusiasm. Without Sadat’s open and passionate conviction. Whereas the former defied the entire Arab world by making a state visit to Jerusalem, the latter went there only for the funeral of Ytzhak Rabin, in November1995. In profoundly different circumstances, with Mubarak having only recently managed to re-enter the diplomatic manoeuvres surrounding the Oslo Agreements (from which he had been excluded). And in a regional context where the impetuous winds of change of Oslo, the handshake between Yasser Arafat and Ytzhak Rabin, and the 1991 Gulf War, had long since petered out. Mubarak has always done his duty towards the alliance with America, but without overdoing things. Indeed, especially in the second part of his first 2 decades in power, being always careful not to lose touch with the mood of the Egyptian man in the street and shifts in the internal political situation, in contrast to Anwar el Sadat, who paid with his life for his inability to understand what was happening in radical Islamic circles. To use the words of Ali Hillal Dessouki, on a national level Mubarak’s foreign policy “did not replace Sadat’s, but worked paralleled to it, with the aim of balancing the side-effects of his predecessor’s policies”. During the 1990’s in particular, the relationship with the United States was strained by major shifts within Egyptian society, which underwent an Islamic revival that – despite the regime’s efforts to restrain it – imposed socio-political restraints on the Egyptian government that had previously been inexistent or at any rate negligible. The season of radical Islamic terrorism (directed above all against tourists and Israeli objectives), and the ambivalent relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood (only formally illegal), has put a brake on the United State’s powerful influence over Egypt, to the point of creating a chasm between the regime’s pro-American stance and the widespread and intense anti-Americanism within society. From this has stemmed a kind of self-censorship in Mubarak’s presidency regarding choices to do with religious observations or foreign policy. At the same time, on an economic level, the system of cliquish favouritism adopted by Mubarak has disillusioned American expectations of rapid and virtuous privatisations in Egyptian industry, still encumbered by clogging Nasserite mechanisms.

During the 1990’s in particular, the relationship with the United States was strained by major shifts within Egyptian society, which underwent an Islamic revival that – despite the regime’s efforts to restrain it – imposed socio-political restraints on the Egyptian government that had previously been inexistent or at any rate negligible. The season of radical Islamic terrorism (directed above all against tourists and Israeli objectives), and the ambivalent relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood (only formally illegal), has put a brake on the United State’s powerful influence over Egypt, to the point of creating a chasm between the regime’s pro-American stance and the widespread and intense anti-Americanism within society. From this has stemmed a kind of self-censorship in Mubarak’s presidency regarding choices to do with religious observations or foreign policy. At the same time, on an economic level, the system of cliquish favouritism adopted by Mubarak has disillusioned American expectations of rapid and virtuous privatisations in Egyptian industry, still encumbered by clogging Nasserite mechanisms. Mubarak has always tried to walk a tightrope between a society increasingly resentful of American influence on the one hand, and his special relationship with Washington on the other. And he has done so by seeking a less subservient role for Egypt than Sadat had envisioned. This meant steering a middle course. Which is what Mubarak did from the beginning. The first symptoms of this change in the course of bilateral relations and regional politics became evident from early in his presidency. To be precise, from shortly after the handing-over of the Sinai Peninsular by Israel. Once this issue had been resolved, apart from the dispute over Taba, by 1982 the new Egyptian president was already demonstrating that the relationship with the United States would no longer entirely follow the patron-client formula. What sparked the process was the Israeli government’s launching of its Operation Peace in Galilee in 1982, with the attack on the Lebanon and the PLO bases in the Land of the Cedars.

Mubarak has always tried to walk a tightrope between a society increasingly resentful of American influence on the one hand, and his special relationship with Washington on the other. And he has done so by seeking a less subservient role for Egypt than Sadat had envisioned. This meant steering a middle course. Which is what Mubarak did from the beginning. The first symptoms of this change in the course of bilateral relations and regional politics became evident from early in his presidency. To be precise, from shortly after the handing-over of the Sinai Peninsular by Israel. Once this issue had been resolved, apart from the dispute over Taba, by 1982 the new Egyptian president was already demonstrating that the relationship with the United States would no longer entirely follow the patron-client formula. What sparked the process was the Israeli government’s launching of its Operation Peace in Galilee in 1982, with the attack on the Lebanon and the PLO bases in the Land of the Cedars.

At that point Mubarak’s foreign policy began to move in parallel with the unfolding of events and the reaction of Egyptian public opinion, which for the first time was able to follow on television the developments in the Lebanese conflict. Mubarak immediately condemned the Israeli aggression, despite Egypt still being an outcast in regional politics due to its expulsion from the Arab League after the unilateral peace treaty with Israel. Really it was Israel’s attack that offered Cairo its first chance to mend relations with the Arab world, to the point where Mubarak requested holding a summit between all the nations in the region. Later, when events became intolerable for Egyptian public opinion, Mubarak took stronger action, withdrawing his ambassador from Tel Aviv. The subsequent massacres in Sabra and Shatila, and Arafat and the PLO’s exile from Beirut, contributed to the continuation of this hard-line stance. To be more precise, Hosni Mubarak’s relationship with Abu Ammar in those circumstances was the sign of the first partial rehabilitation of Egypt by the Arab nations, immortalised in the arrival in the Suez Canal of the Odysseus Elytis from Beirut, in Arafat’s disembarking at Ismailia, and in his encounter with Mubarak in a Cairo where long before he had been a student and a refugee. An encounter which signalled simultaneously both the end of the six year freeze in relations between the Egyptian leadership and the PLO, and the end of the Arab embargo on Egypt after Camp David. The relationship with Arafat, who had always preferred Egypt as a sponsor rather than the fluctuating Jordan of King Hussein, stood up to the strains imposed by incidents such as the hijacking of the Achille Lauro, in which Egypt – instead of putting at risk its relations with the Palestinians – preferred to put at risk its alliance with the United States. It was not easy for Washington to digest the tensions caused by Egypt’s mediation and by Cairo’s attempt to fly Abul Abbas and the hijackers to Tunis on an Egyptian aircraft. Just as for Cairo, and for Rome, it was not easy to digest the Sigonella incident. Basically, anyway, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was one of the trampolines (if not the main one) that Mubarak’s Egypt used to return to the Arab fold. It is no coincidence that Cairo’s definitive readmission to the Arab League came about in 1989, after the first Intifada and the open and undercover diplomatic contacts between Egypt and the PLO, carried out in spite of American worries about the repercussions on Israeli-Egyptian relations. Expert opinion is unanimous that the relationship between Egypt and the United States has always existed within the context of an Egypt-United States-Israel triangle, in which Cairo is the weakest side of the geometrical figure. Until Egypt’s self-appointed role as broker between Israeli and Palestinian adversaries recently assumed a profile more acceptable to the Americans, Washington had always feared that the relationship between Cairo and the PLO might go against Israeli interests. Despite the fact that Palestinian autonomy was one of the objectives of the peace with Israel negotiated by Jimmy Carter.

To be more precise, Hosni Mubarak’s relationship with Abu Ammar in those circumstances was the sign of the first partial rehabilitation of Egypt by the Arab nations, immortalised in the arrival in the Suez Canal of the Odysseus Elytis from Beirut, in Arafat’s disembarking at Ismailia, and in his encounter with Mubarak in a Cairo where long before he had been a student and a refugee. An encounter which signalled simultaneously both the end of the six year freeze in relations between the Egyptian leadership and the PLO, and the end of the Arab embargo on Egypt after Camp David. The relationship with Arafat, who had always preferred Egypt as a sponsor rather than the fluctuating Jordan of King Hussein, stood up to the strains imposed by incidents such as the hijacking of the Achille Lauro, in which Egypt – instead of putting at risk its relations with the Palestinians – preferred to put at risk its alliance with the United States. It was not easy for Washington to digest the tensions caused by Egypt’s mediation and by Cairo’s attempt to fly Abul Abbas and the hijackers to Tunis on an Egyptian aircraft. Just as for Cairo, and for Rome, it was not easy to digest the Sigonella incident. Basically, anyway, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was one of the trampolines (if not the main one) that Mubarak’s Egypt used to return to the Arab fold. It is no coincidence that Cairo’s definitive readmission to the Arab League came about in 1989, after the first Intifada and the open and undercover diplomatic contacts between Egypt and the PLO, carried out in spite of American worries about the repercussions on Israeli-Egyptian relations. Expert opinion is unanimous that the relationship between Egypt and the United States has always existed within the context of an Egypt-United States-Israel triangle, in which Cairo is the weakest side of the geometrical figure. Until Egypt’s self-appointed role as broker between Israeli and Palestinian adversaries recently assumed a profile more acceptable to the Americans, Washington had always feared that the relationship between Cairo and the PLO might go against Israeli interests. Despite the fact that Palestinian autonomy was one of the objectives of the peace with Israel negotiated by Jimmy Carter. The fact is that Egypt has never warmed to peace with Israel. It has always tried to camouflage the peace, both through its privileged relation with the Palestinians and through gestures aimed at reducing internal opposition from Nasserites and Islamic fundamentalists, the main anti-Israeli hardliners. Over the years these gestures have been numerous, recurring every time the brief periods of optimism broke down into periods of violence and outrage. In those phases Mubarak has always been ready to launch anti-Israeli signals for local consumption, such as convoking the Arab League in the most difficult moments (as he did after the election of Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996) or recalling the Egyptian ambassador in Tel Aviv (the last time was after the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada in 2000). Signals perhaps insufficient for an Egyptian public ever less willing to pardon Israeli policies. But necessary to Mubarak in order to appease anger on the streets and, at the same time, avoiding over-irritating the American ally.

The fact is that Egypt has never warmed to peace with Israel. It has always tried to camouflage the peace, both through its privileged relation with the Palestinians and through gestures aimed at reducing internal opposition from Nasserites and Islamic fundamentalists, the main anti-Israeli hardliners. Over the years these gestures have been numerous, recurring every time the brief periods of optimism broke down into periods of violence and outrage. In those phases Mubarak has always been ready to launch anti-Israeli signals for local consumption, such as convoking the Arab League in the most difficult moments (as he did after the election of Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996) or recalling the Egyptian ambassador in Tel Aviv (the last time was after the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada in 2000). Signals perhaps insufficient for an Egyptian public ever less willing to pardon Israeli policies. But necessary to Mubarak in order to appease anger on the streets and, at the same time, avoiding over-irritating the American ally.  The Palestinian conflict has however been only one of the testing-grounds, as well as one of the priorities, in relations between the United States and Egypt. And when we shift our attention from the area of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to that of inter-Arab relations we find that Egypt’s role and function in American strategy change dramatically. This is the context in which Mubarak plays to the full – and without ambiguity – the part of the USA’s most important ally in the region. The most obvious and revealing example is the whole operation undertaken by Mubarak before, during, and after the 1991 Gulf War, which was also the Egyptian president’s opportunity to express his ambivalent strategy towards the United States. A policy which, especially during the twenty years between 1981 and 2001, would give him a significant role to play at the various diplomatic negotiations in which he has participated.

The Palestinian conflict has however been only one of the testing-grounds, as well as one of the priorities, in relations between the United States and Egypt. And when we shift our attention from the area of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to that of inter-Arab relations we find that Egypt’s role and function in American strategy change dramatically. This is the context in which Mubarak plays to the full – and without ambiguity – the part of the USA’s most important ally in the region. The most obvious and revealing example is the whole operation undertaken by Mubarak before, during, and after the 1991 Gulf War, which was also the Egyptian president’s opportunity to express his ambivalent strategy towards the United States. A policy which, especially during the twenty years between 1981 and 2001, would give him a significant role to play at the various diplomatic negotiations in which he has participated.

It is at the level of inter-Arab relations, for that matter, that Mubarak has managed to extract as many benefits as possible for his own power at home. From an economic point of view, for example, through the policies followed during the Gulf crisis and war Mubarak succeeded in obtaining – for the Egyptian contingent of 35,000 soldiers in the coalition against Saddam Hussein – recompenses that were fundamental to reinforcing the national economy. The reduction by 50% of Cairo’s international debt, decided by the Paris Club and the USA (50 billion dollars discounted to 25 billion), a new relationship with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Nations boosting the policy of Egyptian emigration in the Arabian peninsular, new investments in Egypt by the Saudis and the Emirates. From a political point of view also, Mubarak succeeded in creating a decisive role for himself, to the point where, just one year after its readmission to the Arab League, Egypt found itself guiding the whole region and even improving its relations with a Syria willing to enter the anti-Iraq coalition. A leader who had seemed colourless when compared to Sadat’s daring flair in the end proved capable – without at that time losing the support of public opinion at home – of supporting Iraq as an anti-Iranian force during the first Gulf War (as originally requested by the Americans) and then, after just three years, supplying the United States with an enlarged coalition as an anti-Iraq force. Reconstructing and maintaining, at the same time, a highly respected status among the Arab nations and obliterating from his passport the image of a country submissive to America’s will.

From a political point of view also, Mubarak succeeded in creating a decisive role for himself, to the point where, just one year after its readmission to the Arab League, Egypt found itself guiding the whole region and even improving its relations with a Syria willing to enter the anti-Iraq coalition. A leader who had seemed colourless when compared to Sadat’s daring flair in the end proved capable – without at that time losing the support of public opinion at home – of supporting Iraq as an anti-Iranian force during the first Gulf War (as originally requested by the Americans) and then, after just three years, supplying the United States with an enlarged coalition as an anti-Iraq force. Reconstructing and maintaining, at the same time, a highly respected status among the Arab nations and obliterating from his passport the image of a country submissive to America’s will.  Through his inter-Arab policies Mubarak has also managed to obtain, at least in his first years, and to a reasonable extent, public support at home. Partly because of Egypt recovering its original role as the centre of the Arab League, lost under Sadat. Partly because of being able to combine pro-American policies with his regime’s tolerance of the ever-growing social and religious conservatism in the country. This aspect becomes even clearer if we look at how the sending of 35,000 Egyptian soldiers to Saudi Arabia was rendered acceptable to a public opinion which, on the one hand, was reminded of its resentment towards Saddam Hussein over the question of Egyptian migrant workers in Iraq, and on the other was persuaded to accept the justifications offered for Egypt’s participation in a coalition guided by a non-Muslim nation like the USA and stationed close to Islam’s most sacred sites. The most effective support for Mubarak’s line during the Second Gulf War came from the most popular preacher in the country, Al Sha’rawi, who clarified that prophet Mohammed had also appealed to infidels to defend the holy sites, because “God makes the truth triumph over impiety, even when he uses impiety to do so”.The Muslim Brotherhood’s opposition, after some initial ambiguity, to Egypt’s participation in the anti-Iraq coalition has caused considerable problems for Mubarak’s regime, forcing it after the war to dilute American requests for a regional security agreement and to flatly turn down any hypothesis of stationing American troops in bases on Egyptian soil. The increasing distaste of the population of Egypt for American policies in the Middle East and North Africa has grown still more intense from the mid 1990’s, spurred by the Anglo-American intervention in Iraq in 1998 and by the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada in the autumn of 2000. Since the final years of the nineties it has become ever more difficult for Mubarak to distinguish, in the public’s perception, the table of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from the table of inter-Arab relations, in order to demonstrate a non-subordinate relationship with Washington. From the moment that these two levels of Egyptian foreign policy have become inseparable, Mubarak has had increasing problems in justifying his alliance with the United States.

Through his inter-Arab policies Mubarak has also managed to obtain, at least in his first years, and to a reasonable extent, public support at home. Partly because of Egypt recovering its original role as the centre of the Arab League, lost under Sadat. Partly because of being able to combine pro-American policies with his regime’s tolerance of the ever-growing social and religious conservatism in the country. This aspect becomes even clearer if we look at how the sending of 35,000 Egyptian soldiers to Saudi Arabia was rendered acceptable to a public opinion which, on the one hand, was reminded of its resentment towards Saddam Hussein over the question of Egyptian migrant workers in Iraq, and on the other was persuaded to accept the justifications offered for Egypt’s participation in a coalition guided by a non-Muslim nation like the USA and stationed close to Islam’s most sacred sites. The most effective support for Mubarak’s line during the Second Gulf War came from the most popular preacher in the country, Al Sha’rawi, who clarified that prophet Mohammed had also appealed to infidels to defend the holy sites, because “God makes the truth triumph over impiety, even when he uses impiety to do so”.The Muslim Brotherhood’s opposition, after some initial ambiguity, to Egypt’s participation in the anti-Iraq coalition has caused considerable problems for Mubarak’s regime, forcing it after the war to dilute American requests for a regional security agreement and to flatly turn down any hypothesis of stationing American troops in bases on Egyptian soil. The increasing distaste of the population of Egypt for American policies in the Middle East and North Africa has grown still more intense from the mid 1990’s, spurred by the Anglo-American intervention in Iraq in 1998 and by the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada in the autumn of 2000. Since the final years of the nineties it has become ever more difficult for Mubarak to distinguish, in the public’s perception, the table of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from the table of inter-Arab relations, in order to demonstrate a non-subordinate relationship with Washington. From the moment that these two levels of Egyptian foreign policy have become inseparable, Mubarak has had increasing problems in justifying his alliance with the United States. The overall picture that emerges from these few observations tells us that, when all is said and done, the balance of pros and cons in the relationship between the United States and Egypt has benefited both parties. If, however, we concentrate on the consequences that Cairo’s relation with Washington between 1991 and 2001 has had on the situation inside Egypt, we realise that the price paid by Hosni Mubarak’s regime has been high. The nation that set out to be the champion of Arab moderation, in the sense of a focal point for a solid relationship with the Western world, has turned out to be a nation whose 25 years of alliance with the United States has increased its own internal weakness. Both from an institutional viewpoint, with the emergence of an autocracy, and from a socio-political point of view, with the failure to carry out the democratic reforms requested by, among others, Washington. The Mubarak regime’s internal weakness has also had repercussions on its standing in the Arab world, distinguished at times by the president’s undeniable capacity for mediating between the profound divisions within the Arab League, and at others by his inability, especially in recent years, to exert any influence on American policy in the Middle East. et paf! Peace out, Greg

The overall picture that emerges from these few observations tells us that, when all is said and done, the balance of pros and cons in the relationship between the United States and Egypt has benefited both parties. If, however, we concentrate on the consequences that Cairo’s relation with Washington between 1991 and 2001 has had on the situation inside Egypt, we realise that the price paid by Hosni Mubarak’s regime has been high. The nation that set out to be the champion of Arab moderation, in the sense of a focal point for a solid relationship with the Western world, has turned out to be a nation whose 25 years of alliance with the United States has increased its own internal weakness. Both from an institutional viewpoint, with the emergence of an autocracy, and from a socio-political point of view, with the failure to carry out the democratic reforms requested by, among others, Washington. The Mubarak regime’s internal weakness has also had repercussions on its standing in the Arab world, distinguished at times by the president’s undeniable capacity for mediating between the profound divisions within the Arab League, and at others by his inability, especially in recent years, to exert any influence on American policy in the Middle East. et paf! Peace out, Greg

Find below a very interesting piece of article (written by Paola Caridi www.lettera22.it form the independent journalist association) to give you a better insight on the extremely complex situation in the middle east, and the difficult and strategic relationship with the US. I added a couple of pictures of the recent trips to relax your eyes and (hopefully) make you jealous...hehe

Nation of strategic importance. Element of regional stability. In the view of American foreign policy for the Middle East and North Africa over the last thirty years, Egypt has merited mostly flattering comments on the regional role it has played. And all things considered, the compliments have reflected what Egypt has really meant to the USA’s political strategies towards the Middle East, the Arab nations, and the whole region. Including Iran. If only because, in that part of the world, the alliance with Egypt has been the most important and most unexpected diplomatic success, the Department of State and the White House’s prize exhibit from the last fifty years. Made possible, for the most part, by the presence as Egyptian leader of a statesman capable of making astonishing choices, Anwar el Sadat. Protagonist of a drastic change in alliance after the 1973 war, and of an equally sudden abandonment of traditional Nasserite foreign policy which had as its three fundamental pillars the Soviet Union, the Non-Aligned movement, and pan-Arabism.

Nation of strategic importance. Element of regional stability. In the view of American foreign policy for the Middle East and North Africa over the last thirty years, Egypt has merited mostly flattering comments on the regional role it has played. And all things considered, the compliments have reflected what Egypt has really meant to the USA’s political strategies towards the Middle East, the Arab nations, and the whole region. Including Iran. If only because, in that part of the world, the alliance with Egypt has been the most important and most unexpected diplomatic success, the Department of State and the White House’s prize exhibit from the last fifty years. Made possible, for the most part, by the presence as Egyptian leader of a statesman capable of making astonishing choices, Anwar el Sadat. Protagonist of a drastic change in alliance after the 1973 war, and of an equally sudden abandonment of traditional Nasserite foreign policy which had as its three fundamental pillars the Soviet Union, the Non-Aligned movement, and pan-Arabism. While it is true to say that Sadat’s presence was essential to Washington considering Cairo as its Arabian bridgehead in the Middle East and North Africa, one has to admit that the alliance between the United States and Egypt has succeeded in surviving without Sadat, and above all in surviving various political earthquakes in the region that could have damaged the alliance’s stability and indeed destroyed the entire relationship between Cairo and Washington. But despite initial misgivings, despite the difference in character between himself and Sadat, and the difference between their conceptions of Egypt’s political role, Hosni Mubarak has nonetheless managed to maintain the commitments made by his predecessor. That’s to say, he has managed to preserve the alliance with the United States. Although in different terms than those foreseen by Washington. And it may well be that Washington has benefited from the changes that Mubarak has imposed during his twenty years of rule, in some cases without its ally’s approval.

While it is true to say that Sadat’s presence was essential to Washington considering Cairo as its Arabian bridgehead in the Middle East and North Africa, one has to admit that the alliance between the United States and Egypt has succeeded in surviving without Sadat, and above all in surviving various political earthquakes in the region that could have damaged the alliance’s stability and indeed destroyed the entire relationship between Cairo and Washington. But despite initial misgivings, despite the difference in character between himself and Sadat, and the difference between their conceptions of Egypt’s political role, Hosni Mubarak has nonetheless managed to maintain the commitments made by his predecessor. That’s to say, he has managed to preserve the alliance with the United States. Although in different terms than those foreseen by Washington. And it may well be that Washington has benefited from the changes that Mubarak has imposed during his twenty years of rule, in some cases without its ally’s approval. The relation between Egypt and the United States was founded on certain premises, but these soon evolved in ways that corresponded more to Egypt’s than to America’s strategy. The final balance, after twenty years of Mubarak’s presidency, is nonetheless positive for both partners in the alliance. The United States have had in Egypt the lynchpin of its foreign policy for the region, based on four priorities. Firstly, guaranteeing safe passage for crude oil from the Persian Gulf through the Suez Canal. Secondly, protecting the security of Israel. Thirdly, containing those nations in the region which, at different moments, have most threatened American interests (Iran and Iraq). And finally, during the first half of these twenty years at any rate, limiting the influence of the Soviet Union and exporting the policy of global containment to the Middle East and North Africa.

The relation between Egypt and the United States was founded on certain premises, but these soon evolved in ways that corresponded more to Egypt’s than to America’s strategy. The final balance, after twenty years of Mubarak’s presidency, is nonetheless positive for both partners in the alliance. The United States have had in Egypt the lynchpin of its foreign policy for the region, based on four priorities. Firstly, guaranteeing safe passage for crude oil from the Persian Gulf through the Suez Canal. Secondly, protecting the security of Israel. Thirdly, containing those nations in the region which, at different moments, have most threatened American interests (Iran and Iraq). And finally, during the first half of these twenty years at any rate, limiting the influence of the Soviet Union and exporting the policy of global containment to the Middle East and North Africa. Mubarak’s regime too, from its point of view, has obtained more positive than negative results from maintaining the alliance with the United States. On the one hand, as a reward for its role as a bridgehead, it has continued to benefit from the largest economic aid package dispensed by America in the whole area, indispensable for the country’s internal stability. On the other, in an analysis that is only apparently paradoxical, it has exploited its privileged relation with the Americans to gradually revive and reinforce its own position within the Arab world.

Mubarak’s regime too, from its point of view, has obtained more positive than negative results from maintaining the alliance with the United States. On the one hand, as a reward for its role as a bridgehead, it has continued to benefit from the largest economic aid package dispensed by America in the whole area, indispensable for the country’s internal stability. On the other, in an analysis that is only apparently paradoxical, it has exploited its privileged relation with the Americans to gradually revive and reinforce its own position within the Arab world. All things considered, therefore, this has been an alliance that has given satisfaction to both partners. Despite its ups and downs, and despite the changes which the United States could never have foreseen at the time when Sadat put himself decisively in the American camp and carried out the two principal acts of his presidency: the leap from one side of the Iron Curtain to the other, and the peace with Israel. The Americans could never have imagined that Sadat would have disappeared from the scene so soon, and in such a sudden and tragic way. They therefore witnessed Mubarak’s coming to power with considerable scepticism, based on what they knew of him from his visits to the US as vice-president before Sadat’s assassination. During which Mubarak had shown himself to be quite different from his president. Less brilliant, in the first place, both in public and in private. Among American politicians and political technicians the main fear was that Mubarak “was seen as demanding, somewhat abrasive and unbending”, as Hermann Frederick Eilts has written. The worry was, in other words, that Mubarak would not have honoured the peace with Israel, still in its infancy, and might even have returned to the path set down by Gamel Abdel Nasser.Were these worries founded? History informs us that, as it turns out, Mubarak has respected the commitments made by Sadat, showing an unexpected degree of loyalty. But he has done so without his predecessor’s enthusiasm. Without Sadat’s open and passionate conviction. Whereas the former defied the entire Arab world by making a state visit to Jerusalem, the latter went there only for the funeral of Ytzhak Rabin, in November1995. In profoundly different circumstances, with Mubarak having only recently managed to re-enter the diplomatic manoeuvres surrounding the Oslo Agreements (from which he had been excluded). And in a regional context where the impetuous winds of change of Oslo, the handshake between Yasser Arafat and Ytzhak Rabin, and the 1991 Gulf War, had long since petered out. Mubarak has always done his duty towards the alliance with America, but without overdoing things. Indeed, especially in the second part of his first 2 decades in power, being always careful not to lose touch with the mood of the Egyptian man in the street and shifts in the internal political situation, in contrast to Anwar el Sadat, who paid with his life for his inability to understand what was happening in radical Islamic circles. To use the words of Ali Hillal Dessouki, on a national level Mubarak’s foreign policy “did not replace Sadat’s, but worked paralleled to it, with the aim of balancing the side-effects of his predecessor’s policies”.

All things considered, therefore, this has been an alliance that has given satisfaction to both partners. Despite its ups and downs, and despite the changes which the United States could never have foreseen at the time when Sadat put himself decisively in the American camp and carried out the two principal acts of his presidency: the leap from one side of the Iron Curtain to the other, and the peace with Israel. The Americans could never have imagined that Sadat would have disappeared from the scene so soon, and in such a sudden and tragic way. They therefore witnessed Mubarak’s coming to power with considerable scepticism, based on what they knew of him from his visits to the US as vice-president before Sadat’s assassination. During which Mubarak had shown himself to be quite different from his president. Less brilliant, in the first place, both in public and in private. Among American politicians and political technicians the main fear was that Mubarak “was seen as demanding, somewhat abrasive and unbending”, as Hermann Frederick Eilts has written. The worry was, in other words, that Mubarak would not have honoured the peace with Israel, still in its infancy, and might even have returned to the path set down by Gamel Abdel Nasser.Were these worries founded? History informs us that, as it turns out, Mubarak has respected the commitments made by Sadat, showing an unexpected degree of loyalty. But he has done so without his predecessor’s enthusiasm. Without Sadat’s open and passionate conviction. Whereas the former defied the entire Arab world by making a state visit to Jerusalem, the latter went there only for the funeral of Ytzhak Rabin, in November1995. In profoundly different circumstances, with Mubarak having only recently managed to re-enter the diplomatic manoeuvres surrounding the Oslo Agreements (from which he had been excluded). And in a regional context where the impetuous winds of change of Oslo, the handshake between Yasser Arafat and Ytzhak Rabin, and the 1991 Gulf War, had long since petered out. Mubarak has always done his duty towards the alliance with America, but without overdoing things. Indeed, especially in the second part of his first 2 decades in power, being always careful not to lose touch with the mood of the Egyptian man in the street and shifts in the internal political situation, in contrast to Anwar el Sadat, who paid with his life for his inability to understand what was happening in radical Islamic circles. To use the words of Ali Hillal Dessouki, on a national level Mubarak’s foreign policy “did not replace Sadat’s, but worked paralleled to it, with the aim of balancing the side-effects of his predecessor’s policies”. During the 1990’s in particular, the relationship with the United States was strained by major shifts within Egyptian society, which underwent an Islamic revival that – despite the regime’s efforts to restrain it – imposed socio-political restraints on the Egyptian government that had previously been inexistent or at any rate negligible. The season of radical Islamic terrorism (directed above all against tourists and Israeli objectives), and the ambivalent relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood (only formally illegal), has put a brake on the United State’s powerful influence over Egypt, to the point of creating a chasm between the regime’s pro-American stance and the widespread and intense anti-Americanism within society. From this has stemmed a kind of self-censorship in Mubarak’s presidency regarding choices to do with religious observations or foreign policy. At the same time, on an economic level, the system of cliquish favouritism adopted by Mubarak has disillusioned American expectations of rapid and virtuous privatisations in Egyptian industry, still encumbered by clogging Nasserite mechanisms.

During the 1990’s in particular, the relationship with the United States was strained by major shifts within Egyptian society, which underwent an Islamic revival that – despite the regime’s efforts to restrain it – imposed socio-political restraints on the Egyptian government that had previously been inexistent or at any rate negligible. The season of radical Islamic terrorism (directed above all against tourists and Israeli objectives), and the ambivalent relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood (only formally illegal), has put a brake on the United State’s powerful influence over Egypt, to the point of creating a chasm between the regime’s pro-American stance and the widespread and intense anti-Americanism within society. From this has stemmed a kind of self-censorship in Mubarak’s presidency regarding choices to do with religious observations or foreign policy. At the same time, on an economic level, the system of cliquish favouritism adopted by Mubarak has disillusioned American expectations of rapid and virtuous privatisations in Egyptian industry, still encumbered by clogging Nasserite mechanisms. Mubarak has always tried to walk a tightrope between a society increasingly resentful of American influence on the one hand, and his special relationship with Washington on the other. And he has done so by seeking a less subservient role for Egypt than Sadat had envisioned. This meant steering a middle course. Which is what Mubarak did from the beginning. The first symptoms of this change in the course of bilateral relations and regional politics became evident from early in his presidency. To be precise, from shortly after the handing-over of the Sinai Peninsular by Israel. Once this issue had been resolved, apart from the dispute over Taba, by 1982 the new Egyptian president was already demonstrating that the relationship with the United States would no longer entirely follow the patron-client formula. What sparked the process was the Israeli government’s launching of its Operation Peace in Galilee in 1982, with the attack on the Lebanon and the PLO bases in the Land of the Cedars.

Mubarak has always tried to walk a tightrope between a society increasingly resentful of American influence on the one hand, and his special relationship with Washington on the other. And he has done so by seeking a less subservient role for Egypt than Sadat had envisioned. This meant steering a middle course. Which is what Mubarak did from the beginning. The first symptoms of this change in the course of bilateral relations and regional politics became evident from early in his presidency. To be precise, from shortly after the handing-over of the Sinai Peninsular by Israel. Once this issue had been resolved, apart from the dispute over Taba, by 1982 the new Egyptian president was already demonstrating that the relationship with the United States would no longer entirely follow the patron-client formula. What sparked the process was the Israeli government’s launching of its Operation Peace in Galilee in 1982, with the attack on the Lebanon and the PLO bases in the Land of the Cedars.

At that point Mubarak’s foreign policy began to move in parallel with the unfolding of events and the reaction of Egyptian public opinion, which for the first time was able to follow on television the developments in the Lebanese conflict. Mubarak immediately condemned the Israeli aggression, despite Egypt still being an outcast in regional politics due to its expulsion from the Arab League after the unilateral peace treaty with Israel. Really it was Israel’s attack that offered Cairo its first chance to mend relations with the Arab world, to the point where Mubarak requested holding a summit between all the nations in the region. Later, when events became intolerable for Egyptian public opinion, Mubarak took stronger action, withdrawing his ambassador from Tel Aviv. The subsequent massacres in Sabra and Shatila, and Arafat and the PLO’s exile from Beirut, contributed to the continuation of this hard-line stance.

To be more precise, Hosni Mubarak’s relationship with Abu Ammar in those circumstances was the sign of the first partial rehabilitation of Egypt by the Arab nations, immortalised in the arrival in the Suez Canal of the Odysseus Elytis from Beirut, in Arafat’s disembarking at Ismailia, and in his encounter with Mubarak in a Cairo where long before he had been a student and a refugee. An encounter which signalled simultaneously both the end of the six year freeze in relations between the Egyptian leadership and the PLO, and the end of the Arab embargo on Egypt after Camp David. The relationship with Arafat, who had always preferred Egypt as a sponsor rather than the fluctuating Jordan of King Hussein, stood up to the strains imposed by incidents such as the hijacking of the Achille Lauro, in which Egypt – instead of putting at risk its relations with the Palestinians – preferred to put at risk its alliance with the United States. It was not easy for Washington to digest the tensions caused by Egypt’s mediation and by Cairo’s attempt to fly Abul Abbas and the hijackers to Tunis on an Egyptian aircraft. Just as for Cairo, and for Rome, it was not easy to digest the Sigonella incident. Basically, anyway, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was one of the trampolines (if not the main one) that Mubarak’s Egypt used to return to the Arab fold. It is no coincidence that Cairo’s definitive readmission to the Arab League came about in 1989, after the first Intifada and the open and undercover diplomatic contacts between Egypt and the PLO, carried out in spite of American worries about the repercussions on Israeli-Egyptian relations. Expert opinion is unanimous that the relationship between Egypt and the United States has always existed within the context of an Egypt-United States-Israel triangle, in which Cairo is the weakest side of the geometrical figure. Until Egypt’s self-appointed role as broker between Israeli and Palestinian adversaries recently assumed a profile more acceptable to the Americans, Washington had always feared that the relationship between Cairo and the PLO might go against Israeli interests. Despite the fact that Palestinian autonomy was one of the objectives of the peace with Israel negotiated by Jimmy Carter.

To be more precise, Hosni Mubarak’s relationship with Abu Ammar in those circumstances was the sign of the first partial rehabilitation of Egypt by the Arab nations, immortalised in the arrival in the Suez Canal of the Odysseus Elytis from Beirut, in Arafat’s disembarking at Ismailia, and in his encounter with Mubarak in a Cairo where long before he had been a student and a refugee. An encounter which signalled simultaneously both the end of the six year freeze in relations between the Egyptian leadership and the PLO, and the end of the Arab embargo on Egypt after Camp David. The relationship with Arafat, who had always preferred Egypt as a sponsor rather than the fluctuating Jordan of King Hussein, stood up to the strains imposed by incidents such as the hijacking of the Achille Lauro, in which Egypt – instead of putting at risk its relations with the Palestinians – preferred to put at risk its alliance with the United States. It was not easy for Washington to digest the tensions caused by Egypt’s mediation and by Cairo’s attempt to fly Abul Abbas and the hijackers to Tunis on an Egyptian aircraft. Just as for Cairo, and for Rome, it was not easy to digest the Sigonella incident. Basically, anyway, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was one of the trampolines (if not the main one) that Mubarak’s Egypt used to return to the Arab fold. It is no coincidence that Cairo’s definitive readmission to the Arab League came about in 1989, after the first Intifada and the open and undercover diplomatic contacts between Egypt and the PLO, carried out in spite of American worries about the repercussions on Israeli-Egyptian relations. Expert opinion is unanimous that the relationship between Egypt and the United States has always existed within the context of an Egypt-United States-Israel triangle, in which Cairo is the weakest side of the geometrical figure. Until Egypt’s self-appointed role as broker between Israeli and Palestinian adversaries recently assumed a profile more acceptable to the Americans, Washington had always feared that the relationship between Cairo and the PLO might go against Israeli interests. Despite the fact that Palestinian autonomy was one of the objectives of the peace with Israel negotiated by Jimmy Carter. The fact is that Egypt has never warmed to peace with Israel. It has always tried to camouflage the peace, both through its privileged relation with the Palestinians and through gestures aimed at reducing internal opposition from Nasserites and Islamic fundamentalists, the main anti-Israeli hardliners. Over the years these gestures have been numerous, recurring every time the brief periods of optimism broke down into periods of violence and outrage. In those phases Mubarak has always been ready to launch anti-Israeli signals for local consumption, such as convoking the Arab League in the most difficult moments (as he did after the election of Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996) or recalling the Egyptian ambassador in Tel Aviv (the last time was after the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada in 2000). Signals perhaps insufficient for an Egyptian public ever less willing to pardon Israeli policies. But necessary to Mubarak in order to appease anger on the streets and, at the same time, avoiding over-irritating the American ally.

The fact is that Egypt has never warmed to peace with Israel. It has always tried to camouflage the peace, both through its privileged relation with the Palestinians and through gestures aimed at reducing internal opposition from Nasserites and Islamic fundamentalists, the main anti-Israeli hardliners. Over the years these gestures have been numerous, recurring every time the brief periods of optimism broke down into periods of violence and outrage. In those phases Mubarak has always been ready to launch anti-Israeli signals for local consumption, such as convoking the Arab League in the most difficult moments (as he did after the election of Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996) or recalling the Egyptian ambassador in Tel Aviv (the last time was after the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada in 2000). Signals perhaps insufficient for an Egyptian public ever less willing to pardon Israeli policies. But necessary to Mubarak in order to appease anger on the streets and, at the same time, avoiding over-irritating the American ally.  The Palestinian conflict has however been only one of the testing-grounds, as well as one of the priorities, in relations between the United States and Egypt. And when we shift our attention from the area of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to that of inter-Arab relations we find that Egypt’s role and function in American strategy change dramatically. This is the context in which Mubarak plays to the full – and without ambiguity – the part of the USA’s most important ally in the region. The most obvious and revealing example is the whole operation undertaken by Mubarak before, during, and after the 1991 Gulf War, which was also the Egyptian president’s opportunity to express his ambivalent strategy towards the United States. A policy which, especially during the twenty years between 1981 and 2001, would give him a significant role to play at the various diplomatic negotiations in which he has participated.

The Palestinian conflict has however been only one of the testing-grounds, as well as one of the priorities, in relations between the United States and Egypt. And when we shift our attention from the area of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to that of inter-Arab relations we find that Egypt’s role and function in American strategy change dramatically. This is the context in which Mubarak plays to the full – and without ambiguity – the part of the USA’s most important ally in the region. The most obvious and revealing example is the whole operation undertaken by Mubarak before, during, and after the 1991 Gulf War, which was also the Egyptian president’s opportunity to express his ambivalent strategy towards the United States. A policy which, especially during the twenty years between 1981 and 2001, would give him a significant role to play at the various diplomatic negotiations in which he has participated.

It is at the level of inter-Arab relations, for that matter, that Mubarak has managed to extract as many benefits as possible for his own power at home. From an economic point of view, for example, through the policies followed during the Gulf crisis and war Mubarak succeeded in obtaining – for the Egyptian contingent of 35,000 soldiers in the coalition against Saddam Hussein – recompenses that were fundamental to reinforcing the national economy. The reduction by 50% of Cairo’s international debt, decided by the Paris Club and the USA (50 billion dollars discounted to 25 billion), a new relationship with Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Nations boosting the policy of Egyptian emigration in the Arabian peninsular, new investments in Egypt by the Saudis and the Emirates.

From a political point of view also, Mubarak succeeded in creating a decisive role for himself, to the point where, just one year after its readmission to the Arab League, Egypt found itself guiding the whole region and even improving its relations with a Syria willing to enter the anti-Iraq coalition. A leader who had seemed colourless when compared to Sadat’s daring flair in the end proved capable – without at that time losing the support of public opinion at home – of supporting Iraq as an anti-Iranian force during the first Gulf War (as originally requested by the Americans) and then, after just three years, supplying the United States with an enlarged coalition as an anti-Iraq force. Reconstructing and maintaining, at the same time, a highly respected status among the Arab nations and obliterating from his passport the image of a country submissive to America’s will.

From a political point of view also, Mubarak succeeded in creating a decisive role for himself, to the point where, just one year after its readmission to the Arab League, Egypt found itself guiding the whole region and even improving its relations with a Syria willing to enter the anti-Iraq coalition. A leader who had seemed colourless when compared to Sadat’s daring flair in the end proved capable – without at that time losing the support of public opinion at home – of supporting Iraq as an anti-Iranian force during the first Gulf War (as originally requested by the Americans) and then, after just three years, supplying the United States with an enlarged coalition as an anti-Iraq force. Reconstructing and maintaining, at the same time, a highly respected status among the Arab nations and obliterating from his passport the image of a country submissive to America’s will.  Through his inter-Arab policies Mubarak has also managed to obtain, at least in his first years, and to a reasonable extent, public support at home. Partly because of Egypt recovering its original role as the centre of the Arab League, lost under Sadat. Partly because of being able to combine pro-American policies with his regime’s tolerance of the ever-growing social and religious conservatism in the country. This aspect becomes even clearer if we look at how the sending of 35,000 Egyptian soldiers to Saudi Arabia was rendered acceptable to a public opinion which, on the one hand, was reminded of its resentment towards Saddam Hussein over the question of Egyptian migrant workers in Iraq, and on the other was persuaded to accept the justifications offered for Egypt’s participation in a coalition guided by a non-Muslim nation like the USA and stationed close to Islam’s most sacred sites. The most effective support for Mubarak’s line during the Second Gulf War came from the most popular preacher in the country, Al Sha’rawi, who clarified that prophet Mohammed had also appealed to infidels to defend the holy sites, because “God makes the truth triumph over impiety, even when he uses impiety to do so”.The Muslim Brotherhood’s opposition, after some initial ambiguity, to Egypt’s participation in the anti-Iraq coalition has caused considerable problems for Mubarak’s regime, forcing it after the war to dilute American requests for a regional security agreement and to flatly turn down any hypothesis of stationing American troops in bases on Egyptian soil. The increasing distaste of the population of Egypt for American policies in the Middle East and North Africa has grown still more intense from the mid 1990’s, spurred by the Anglo-American intervention in Iraq in 1998 and by the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada in the autumn of 2000. Since the final years of the nineties it has become ever more difficult for Mubarak to distinguish, in the public’s perception, the table of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from the table of inter-Arab relations, in order to demonstrate a non-subordinate relationship with Washington. From the moment that these two levels of Egyptian foreign policy have become inseparable, Mubarak has had increasing problems in justifying his alliance with the United States.

Through his inter-Arab policies Mubarak has also managed to obtain, at least in his first years, and to a reasonable extent, public support at home. Partly because of Egypt recovering its original role as the centre of the Arab League, lost under Sadat. Partly because of being able to combine pro-American policies with his regime’s tolerance of the ever-growing social and religious conservatism in the country. This aspect becomes even clearer if we look at how the sending of 35,000 Egyptian soldiers to Saudi Arabia was rendered acceptable to a public opinion which, on the one hand, was reminded of its resentment towards Saddam Hussein over the question of Egyptian migrant workers in Iraq, and on the other was persuaded to accept the justifications offered for Egypt’s participation in a coalition guided by a non-Muslim nation like the USA and stationed close to Islam’s most sacred sites. The most effective support for Mubarak’s line during the Second Gulf War came from the most popular preacher in the country, Al Sha’rawi, who clarified that prophet Mohammed had also appealed to infidels to defend the holy sites, because “God makes the truth triumph over impiety, even when he uses impiety to do so”.The Muslim Brotherhood’s opposition, after some initial ambiguity, to Egypt’s participation in the anti-Iraq coalition has caused considerable problems for Mubarak’s regime, forcing it after the war to dilute American requests for a regional security agreement and to flatly turn down any hypothesis of stationing American troops in bases on Egyptian soil. The increasing distaste of the population of Egypt for American policies in the Middle East and North Africa has grown still more intense from the mid 1990’s, spurred by the Anglo-American intervention in Iraq in 1998 and by the beginning of the Al Aqsa Intifada in the autumn of 2000. Since the final years of the nineties it has become ever more difficult for Mubarak to distinguish, in the public’s perception, the table of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from the table of inter-Arab relations, in order to demonstrate a non-subordinate relationship with Washington. From the moment that these two levels of Egyptian foreign policy have become inseparable, Mubarak has had increasing problems in justifying his alliance with the United States. The overall picture that emerges from these few observations tells us that, when all is said and done, the balance of pros and cons in the relationship between the United States and Egypt has benefited both parties. If, however, we concentrate on the consequences that Cairo’s relation with Washington between 1991 and 2001 has had on the situation inside Egypt, we realise that the price paid by Hosni Mubarak’s regime has been high. The nation that set out to be the champion of Arab moderation, in the sense of a focal point for a solid relationship with the Western world, has turned out to be a nation whose 25 years of alliance with the United States has increased its own internal weakness. Both from an institutional viewpoint, with the emergence of an autocracy, and from a socio-political point of view, with the failure to carry out the democratic reforms requested by, among others, Washington. The Mubarak regime’s internal weakness has also had repercussions on its standing in the Arab world, distinguished at times by the president’s undeniable capacity for mediating between the profound divisions within the Arab League, and at others by his inability, especially in recent years, to exert any influence on American policy in the Middle East. et paf! Peace out, Greg

The overall picture that emerges from these few observations tells us that, when all is said and done, the balance of pros and cons in the relationship between the United States and Egypt has benefited both parties. If, however, we concentrate on the consequences that Cairo’s relation with Washington between 1991 and 2001 has had on the situation inside Egypt, we realise that the price paid by Hosni Mubarak’s regime has been high. The nation that set out to be the champion of Arab moderation, in the sense of a focal point for a solid relationship with the Western world, has turned out to be a nation whose 25 years of alliance with the United States has increased its own internal weakness. Both from an institutional viewpoint, with the emergence of an autocracy, and from a socio-political point of view, with the failure to carry out the democratic reforms requested by, among others, Washington. The Mubarak regime’s internal weakness has also had repercussions on its standing in the Arab world, distinguished at times by the president’s undeniable capacity for mediating between the profound divisions within the Arab League, and at others by his inability, especially in recent years, to exert any influence on American policy in the Middle East. et paf! Peace out, Greg

Comments